|

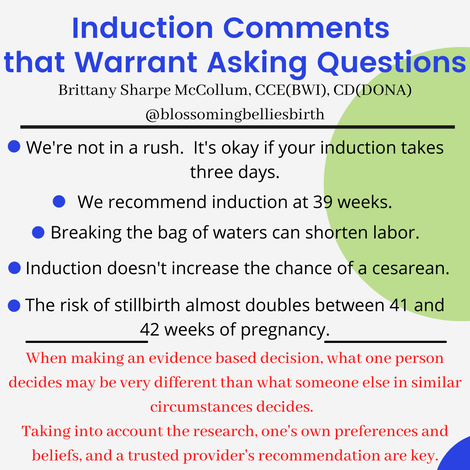

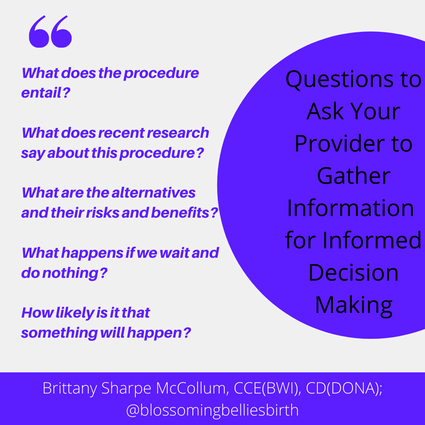

This week our focus is on induction! With our free webinar coming up live on Wednesday March 3rd, it seemed like a great time to review some common statements people hear from their providers and break down the evidence as well as the need to ask questions when faced with these comments because they may not be just as clear cut as they seem. We're not in a rush. It's okay if your induction takes three days. In ideal circumstances, this can be true. There are many factors though that may affect the induction timeline and be quick game changers, including - but not limited to - the water breaking prior to induction, back to back contractions that may limit the safety of other interventions, and pain medication that leads to more quickly increased Pitocin. Also, although this sounds good in theory, in reality, no one is eating well or resting well during an induction and that can lead to a quicker timeline of intervention acceptance or recommendation than previously planned. We recommend induction at 39 weeks. The ARRIVE trial (two great analyses are here: Parsing the ARRIVE Trial: Should First TIme Parents by Induced at 39 Weeks? by Henci Goer, BA and The ARRIVE Trial A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management by Rebecca Dekker, PhD, RN) has led to an increase in recommendation to induce low risk pregnancies in first time parents at 39 weeks. The circumstances of the families being induced in the ARRIVE trial are not recreated in every laboring room with every induction - a slow paced induction - and therefore one cannot expect the same results. In addition, the trial does not take into account those parents that have preferences for low intervention experiences. Consider the research (including average lengths of pregnancy) as well as one's own preferences when making a decision. Breaking the bag of waters can shorten labor. Research shows this to be true when it is done early in the induction process; research does not show a higher rate of cesarean birth or infection (however, known risk factors for increasing risk of infections such as frequency and number of internal exams must be taken into consideration). Breaking the bag of waters is not recommended if the baby is at a -2 station or higher and may carry a greater risk of complication depending on the position of the baby. Research does not show, in a spontaneous labor, that breaking the bag of waters reduces the length of labor. Induction doesn't increase the chance of a cesarean. The ARRIVE trial was so impactful because it was a large study and it refuted all the previous studies that had shown increased risk of cesarean with induction. However, as noted above, the circumstances of the ARRIVE trial are not recreated in most birthing places and therefore one cannot expect the same outcome. When comparing only induction of labor at different gestational ages, research shows an increased rate of cesarean birth with induction of labor with each week that passes. However, when comparing the cesarean rate of induction of labor with spontaneous labor in the same week - regardless of gestational week - research shows a lower rate of cesarean birth among the spontaneous labor group (however, one, of course, cannot "make" spontaneous labor happen so this is a bit like comparing apples and oranges). When making a decision about induction at certain gestational ages, it is important to consider as many risks and benefits as possible in the context of one's preferences to determine the appropriate choice at each gestational week for the individual. The risk of stillbirth almost doubles between 41 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. This statement includes both high risk and low risk pregnancies and is a “relative risk” statement. The statistical risk increases from 1.66 to 3.18 per 1000 births between 41 and 42 weeks of pregnancy (approximately .17 to .32 out of 100). This is approximately a 94% increase which sounds extremely high! However, when considering the numbers and not the percentage of relative risk, the numbers may not seem quite as alarming. The risk after 41 weeks of pregnancy for a low risk person ranges from .8 to 1.66 out of 1000 (.08 to .17 out of 100) based on the birth parent’s risk factors. It is important to remember that certain factors may change this risk (such as age of the birthing person) and also keep in mind that the induction process carries its own risks. Please remember the following when thinking about your choices and comparing them to what others may choose. As parents (and providers), we aim to minimize risk to our children as much as possible. For each person perceived risk may weigh differently in the decision making process. Each person deserves to be given the respect, the research, and the ability to make a decision that feels best to them, and after weighing the pros and cons (in their entirety including risks associated with every intervention and the path of no intervention) they also deserve to have their decisions respected without coercion, guilt, or fear of retaliation. The questions below can be used to have conversations with providers on any intervention related to birth or postpartum. - Brittany Sharpe McCollum, CCE(BWI), CD(DONA) is the owner of Blossoming Bellies Wholistic Birth Services, providing childbirth related services, classes, and workshops to parents and birth professionals in the Philadelphia area and worldwide. Sources:

Bhide Amarnath. Induction of labor and cesarean section. AOGS. Volume100, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 187-188. Davey, MA., King, J. Caesarean section following induction of labour in uncomplicated first births- a population-based cross-sectional analysis of 42,950 births. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 92 (2016). Dekker, Rebecca PhD, RN, APRN, Mimi Niles, CNM, MSN, MPH, PhD student, and Alicia A. Breakey, PhD. Evidence on Advanced Maternal Age. Evidence Based Birth. March 29, 2016. Goldberg, Daphne MD, ABHM, FAAFP, Eva Zasloff MD. Artificial Rupture of Membranes. Integrative Medicine (Second Edition), 2007. Grobman W. A., Rice M. M., Reddy U. M., et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med 2018;379:513-23. Howarth G, Botha DJ. Amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin for induction of labour. Cochrane. 23 July 2001. Muglu, J., Rather, H., Arroyo-Manzano, D., et al. (2019). Risks of stillbirth and neonatal death with advancing gestation at term: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of 15 million pregnancies. PLoS Med 16(7), e1002838. Sun Woo Kim MD, Dimitrios Nasioudis MD, Lisa D.LevineMD, MSCE. Role of early amniotomy with induced labor: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. Volume 1, Issue 4, November 2019, 100052.

1 Comment

|

AuthorAs the Philadelphia birth world blooms bigger and brighter, I think it's time I start putting some of the insightful questions I've received and information I've research into a public journal. I hope you'll find this inspiring, empowering, and totally enjoyable. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed